glen canyon instituteDedicated to the restoration of Glen Canyon and a free flowing Colorado River.

GCI

Philip Hyde

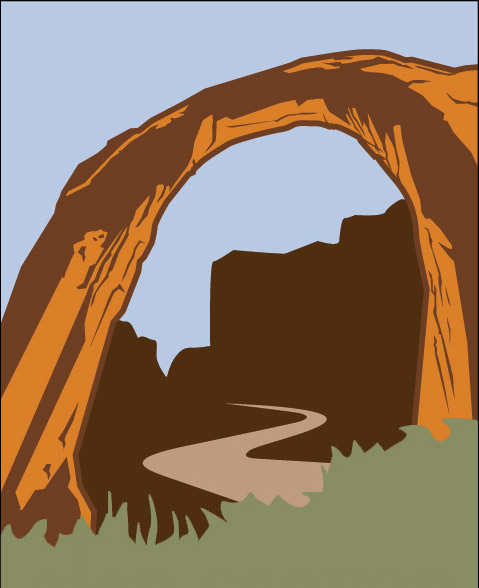

Many people refer to Philip Hyde as the underappreciated master landscape photographer of the 20th Century. His photographs participated in more environmental campaigns than those of any other photographer. At the birth of the modern environmental movement, he was one of the primary illustrators of the groundbreaking Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series. He dedicated his life to defending Western American wilderness, working with the Wilderness Society, National Audubon and others. His color landscapes inspired a generation of photographers, while helping to establish color photography as a fine art. His photographs helped protect Dinosaur National Monument, the Grand Canyon, the Coast Redwoods, Point Reyes, King’s Canyon, Canyon de Chelly, the North Cascades, Canyonlands, the Wind Rivers, Big Sur and many other National Parks and wilderness areas.

American Photo Magazine named Philip Hyde’s photograph, “Cathedral In The Desert, Glen Canyon, Utah, 1964” one of the top 100 photographs of the 20th century. Ansel Adams said that Philip Hyde was “one of the very best photographers of the natural scene in America.” Pulitzer Prize winning photographer Jack Dykinga said, “Philip Hyde inspired many of the ‘Who’s Who’ of Landscape Photography working today.” In Outdoor Photographer and many other magazines, Philip Hyde is referred to as “one of the all-time most influential landscape masters.”

Born and raised in San Francisco, Philip Hyde lived for 50 years in the house he built in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California with his late wife Ardis. At the California School of Fine Art, now the San Francisco Art Institute, Philip Hyde studied under Ansel Adams, Minor White, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Lisette Model, Dorothea Lange and other definers of the medium. Philip Hyde’s work has appeared in more than 80 books and 100 major publications including The New York Times, Audubon, Life, National Geographic, Aperture, B&W Magazine, Fortune and Newsweek. His work has been exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art, George Eastman House, Smithsonian Institute, International Center of Photography, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California Academy of Sciences, Center for Creative Photography, Metropolitan Museum of Art and many others. The North American Nature Photography Association honored him with a lifetime achievement award in 1996. He received the California Conservation Council’s Merit Award in 1962 and the Albert Bender Grant in 1956.

After losing his eyesight in 2000, he relied on dreams for glimpses of the natural world he spent a lifetime defending. His son, David, who walked many wilderness miles with his parents, continues to involve the historically significant photographs in conservation efforts. A portion of proceeds from fine art print sales goes toward environmental causes. David, whose articles have been nationally syndicated, is writing a memoir about his family and blogging about fine art landscape photography.

Gallery generously donated by David Leland Hyde

Philip Hyde Artist’s Statement

Compiled and Edited by David Leland Hyde from Range of Light, Slickrock, Drylands and Other Books, Articles, Posters, Interviews and Portfolios

Rev. January 26, 2010

My intent is not to awe, but to stimulate empathy and love. My basic concern is with what Emerson called ‘the integrity of natural objects.’ I am not interested in pretty pictures for postcards. I feel better if I just get a few people to see something they haven’t seen before. I rarely wait for light or for some missing element, partly because I wish to avoid pouring nature into a mold, but also because waiting for something to happen may well mean missing something else. Black-and-white is excellent experience for color work because it encourages sensitivity to form, texture, tonal gradations and the quality of light. Color photographs that lack these qualities and rely too much on the shock value of color alone will not sustain interest. I begin to see when I leave the car behind. People are ever hurrying over the increasing highways that penetrate lovely country and either lacerate it or pass it by unseen. A mind at peace may be found in any individual or people who have kept touch with what the land is saying and who lack the benefits of instant dissemination of the human troubles that make news. After reading Gandhi, I see that what we need now is a peaceful environmental revolution. The Earth will survive, but will man survive on the Earth?