glen canyon instituteDedicated to the restoration of Glen Canyon and a free flowing Colorado River.

GCI

Greater Glen Canyon: Bears Ears and Grand Staircase Escalante

Greater Glen Canyon: Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments

To see how you can help, please read the “Take Action” section at the bottom of this page.

The heart of Glen Canyon is in the Colorado River corridor below its confluence with the Green River, where it joins the San Juan, Escalante, and Dirty Devil Rivers. But the ecosystem of Greater Glen Canyon expands well beyond, connecting hundreds of square miles of tributaries and canyons that feed into the main river system. Two of the most important segments of Greater Glen Canyon are the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments, lying directly to the east and west of Glen Canyon, respectively.

These National Monuments are especially important to those who care about the health of the Colorado River ecosystem. They contain much of the Glen Canyon watershed, so the air and water quality, wildlife habitats, scenery, and wilderness of these lands are critical to the integrity of Glen Canyon itself. Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments are essential to keeping these values intact.

In December 2017, President Donald Trump issued a proclamation reducing Bears Ears National Monument by 85%, and Grand Staircase-Escalante by 50%. This unprecedented and likely illegal action by the president was made with the clear intent of opening up the region to increased coal, oil, natural gas, and uranium extraction. These two national monuments, in their full, original size encompassing 3,232,310 acres, are crucial to the protection of the access, ecology, and watershed of Glen Canyon and the Colorado River. Shrinking and opening these monuments to exploitation is an attack on the integrity of the Greater Glen Canyon ecosystem.

BACKGROUND

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was established in 1996 by president Bill Clinton using the authority of the Antiquities Act. In its original size, the monument encompassed 1.8 million acres of land, bordering the east side of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The region is home to some of the most remote land in the United States, and some of the most important archeological and paleontological sites in the country. It’s been called “Dinosaur Shangi-La” for its large volume of fossils from the Cretaceous period, which are rarely found in such well-preserved form. The monument was home to over 20,000 archeological sites, as well as hundreds of species of plants and animals.

Once an expansive national monument spanning from the Escalante River drainage in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, to the Kaiparowits Plateau, to the boundaries of Bryce Canyon and Capitol Reef National Parks, the “new” monument boundaries have been shrunken to three small, scattered units. The BLM is quickly pushing to draft management plans before the end of the year, with only a few meetings in nearby towns. The 1996 monument plan involved 17 meetings across several states, and took over 3 years.

Bears Ears National Monument was designated by President Barack Obama in 2016. The 1.4 million acre monument designation was a smaller version of a 1.9 million acre monument originally proposed by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. The designation of Bears Ears National Monument came only after many decades of work by these tribes Native American Tribes and conservation groups. In the 21st century, some of these lands have been proposed as an expansion of Canyonlands National Park, as a part of a Greater Canyonlands National Monument, and as a Cedar Mesa national monument or conservation area. All of these proposals were thwarted by the opposition of entrenched resource development and anti-public land interests.

In 2013, Congressman Rob Bishop of Utah, the chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, announced his Public Lands Initiative (PLI). The PLI was supposed to bring diverse “stakeholders” together in a “grand bargain” that would determine the future of the public lands of the region. Several years of meetings were held with co

unty commissioners, fossil fuel and mining industries, ranchers, tribes, and conservation groups. However, the final proposal released in 2016 would have opened the vast majority of the region to resource extraction, industrial exploitation, off-road motorized recreation, and other destructive uses.

Not surprisingly, this plan was almost universally rejected by protection advocates. The deal was also opposed by anti-environmental interests, which could not accept even the small, scattered, and poorly protected “conservation” areas in the PLI. A bill to authorize the PLI was introduced in Congress in 2016, but it did not pass and has not yet been reintroduced in the current Congress.

The advocates of Bears Ears National Monument took a different approach than past protection efforts.This proposal was developed by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, which includes representatives of the Hopi Nation, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah Ouray and Zuni Tribe, in collaboration with conservationists, businesses, and other constituencies. It envisioned management of the area as a cooperative effort between the federal land agencies and the tribes, which would strengthen protection for the area while honoring and providing for Native American traditions.

The Bears Ears proposal immediately met with strong opposition from the same interests that obstructed past protection efforts. This time, however, advocates did an excellent job of generating broad public awareness and support across Utah and the country. This convinced President Obama to designate the Bears Ears monument, despite the aggressive opposition.

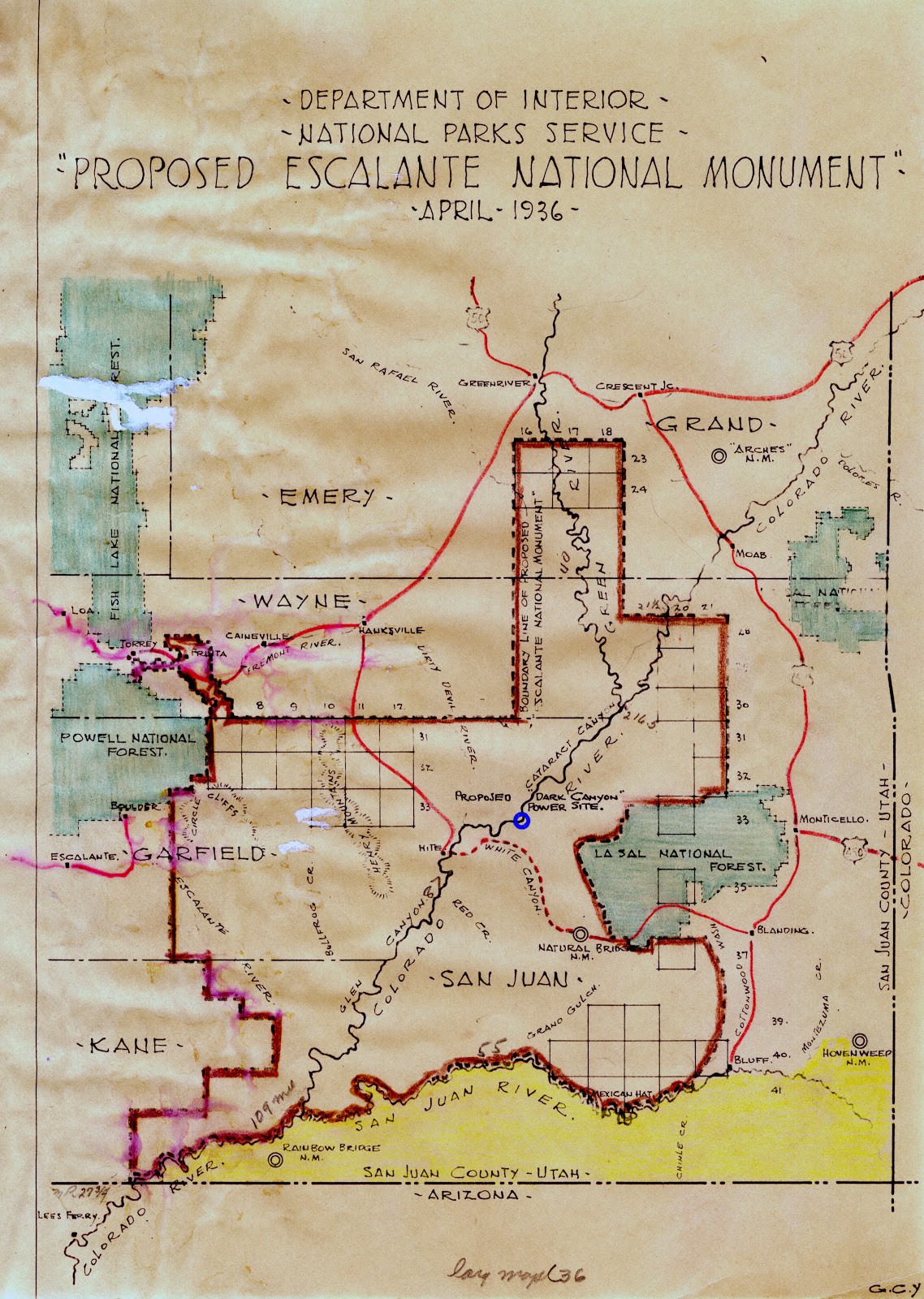

While the creation of these monuments didn’t occur until recent decades, the idea dates back to 1936 when then Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes, proposed the 6,968 square mile “Escalante National Monument”. This vast monument would have encompassed all of Glen Canyon, the Green and Colorado Rivers above their confluence, Cataract Canyon, the San Juan River, and large portions of what later became Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments. The proposal met opposition from Utah lawmakers, and was altered to be a less-protected National Recreation Area. Even that proposal failed to make it out of committee in Congress, and was ultimately forgotten as World War II began.

THREATS

Energy Development

While Utah policy makers have repeatedly claimed the fight against the monuments wasn’t about mineral extraction, exposed email threads now show that oil, gas, coal, and uranium extraction was always a driving factor. Several contentious areas in the original 1.9-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument proposal were deleted by President Obama to try to appease monument opponents. This includes areas that were left unprotected in Bishop’s PLI plan, such as the Abajo Mountains, Allen Canyon, Black Mesa, Wingate Mesa, Nokai Dome, and the Deneros Uranium Mine — which is poised to expand its toxic footprint tenfold. As of March 1, 2018 the BLM has permitted expansion for these mines.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is at a greater risk for mineral extraction on a wider scale. Much of the monument sits on top of the Kaiparowits Plateau coal deposits, one of the largest in the country. The redrawn monument borders omit the plateau, allowing access to this coal layer and reopening a battle that conservationists fought back in the 1990s.

Watershed

Downgrading Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante has put the Greater Glen Canyon watershed at serious risk. Many of the drainages in the region see infrequent seasonal flows in the form of flash floods. In areas with oil, gas, and mining operations, flash floods can pose a serious risk to river drainages by flushing contaminants downstream. Both Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante drain into the Colorado River through Glen Canyon, making these drainages and side canyons critical components of Glen Canyon’s habitat, which is rebounding after decades of flooding by Lake Powell reservoir. Such ecosystems are best protected through carefully managed recreation near creeks and drainages; and by limiting as much as possible any oil, gas, and mineral extraction upstream. The health of the entire ecosystem, including plants and animals, relies on a healthy watershed.

Looting and Vandalism

The majority of Bears Ears National Monument is on land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), whose top priority is resource extraction and development. Protection of the natural and cultural integrity of these lands has been a low priority. As a result, this region has been subject to looting and desecration of Native American artifacts and cultural sites for decades. Archeological looting and vandalism was one of the primary drivers behind the monument designation. Instead of the loose and ambiguous BLM and local enforcement against looting, the monument status was meant to give greater protection to Native American cultural and archeological sites.

Preservation of Experience

Aside from the physical impacts to the land and the water, national monument status helps protect the heritage and quality of outdoor experiences for future generations. Throughout the history of the West, our national parks, monuments, and wilderness areas have provided a framework for preserving the unique natural qualities and recreational experiences of the region’s most spectacular landscapes. Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Canyonlands National Park are shining examples of how it is possible to both protect both the quality of the backcountry and to benefit the local economy. Under Trump’s proclamations, the newly downsized monuments would only be managed by local county authorities, with little consideration given to management planning. As a result, it is almost certain that these areas will suffer from weaker protection of trails and trailheads, insufficient regulation of off-road motor vehicles, unclear signage, a lack of public education programs, and underfunded and understaffed visitor centers.

One of the most popular Glen Canyon trail access roads along the Escalante River is Hole in The Rock Road. This historic and rugged dirt road was deliberately omitted from the new monuments carved from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, with a clear intent of allowing new development and paving. If the state is allowed to pave and further develop the road — an irreplaceable part of Utah’s pioneer heritage — would drastically increase tourist traffic to the remote region and invite increased illegal off-road motorized use, which would threaten the fragile ecosystem and degrade the remote and primitive experience for visitors to the area.

Take Action

Comments to submit before 11/15/2018

Bears Ears

- Comments are on the draft resource management plan for lands excluded from Bears Ears National Monument under Presidential Proclamation 9681 and for lands remaining under national monument status.

- The BLM should halt the current planning process until the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia makes a definitive ruling on the legality of Presidential Proclamation 9681. The legal challenges to the Proclamation are being made by a number of credible organizations. If the court rules to reverse the Proclamation, the time and taxpayer dollars spent on the planning process will have been wasted.

- By removing protection for 1,148,124 acres of land from the original national monument, Proclamation 9681 will endanger the ecological, historic, geological, and cultural values for which Bears Ears National Monument was designated under Proclamation 9558 in 2016.

- If the BLM continues the planning process, any resulting management plans must reflect the original intent and protections of Proclamation 9558, which designated the original monument in 2016, by safeguarding the nationally significant ecological, historic, geological, and cultural values cited in Proclamation 9558 and located within the original boundaries of the monument.

- Call on the BLM to cancel the planning process until the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia can rule on Presidential Proclamation 9681 and in the meantime, continue to provide protections for all 1.35 million acres in the original monument designated under Proclamation 9558 of 2016.

- Briefly describe any personal connections or experiences that make the protection of the entire original Bears Ears National Monument important to you.

Comments are being accepted until November 15, 2018. You can email your comments online to:

blm_ut_monticello_monuments@blm.gov

or by mail to:

Bureau of Land Management

Canyon Country District Office

Attention: Lance Porter

82 East Dogwood

Moab, Utah 84534

For more information on the planning process, visit this page:

You can review the Draft Monument Management Plans and Environmental Impact Statement, Shash Jaa and Indian Creek and Units of Bears Ears National Monument and other planning documents here:

Grand Staircase-Escalante

- Comments are on the draft resource management plan for lands excluded from the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument under Presidential Proclamation 9682 and for lands remaining under national monument status.

- The BLM should halt the current planning process until the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia makes a definitive ruling on the legality of Presidential Proclamation 9682. The legal challenges to the Proclamation are being made by a number of credible organizations. If the court rules to reverse the Proclamation, the time and taxpayer dollars spent on the planning process will have been wasted.

- By removing protection for 861,974 acres of land from the original national monument, Proclamation 9682 will endanger the ecological, historic, geological, and cultural values for which Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was designated under Proclamation 9558 in 1996.

- If the BLM continues the planning process, any resulting management plans must reflect the original intent and protections of Proclamation 6920, which designated Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in 1996, by safeguarding the nationally significant ecological, historic, geological, and cultural values cited in Proclamation 6920 and located within the original boundaries of the monument.

- Call on the BLM to cancel the planning process until the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia can rule on Presidential Proclamation 9682 and in the meantime, continue to provide protections for all 1.35 million acres in the original monument designated under Proclamation 6920 of 1996.

- Briefly describe any personal connections or experiences that make the protection of the entire original Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument important to you.

Comments are being accepted until November 30, 2018. You can submit your comments online here:

or by mail to:

Bureau of Land Management

669 S Hwy 89A

Kanab, UT 84741

You can review the Draft Resource Management Plans and Environmental Impact Statement for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Kanab-Escalante Planning Area and other planning documents here:

—

Greater Glen Canyon is under attack. Multiple lawsuits have been filed challenging the president’s downsizing of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments, but these areas are currently susceptible to the threats listed above. Both original monuments went through a rigorous process of scoping and management collaboration, but the newly drafted monument boundaries have undergone a hastily thrown-together management plan with very little public input.

H.R. 4532 & H.R. 4532

Since President Trump’s executive order, both monuments have been threatened by Utah lawmakers. Congressmen Chris Stewart and John Curtis have introduced bills that would make the reductions permanent. Rep. Stewart’s H.R. 4558 makes President Clinton’s order on Grand Staircase-Escalante “null and void” and largely turns management of the lands over to county and state control. It creates drastically smaller monuments within the original area. Similarly, Rep. Curtis’ bill, H.R. 4532 creates smaller units snipped out of the original plan. These pieces of legislation are thinly disguised efforts to codify President Trump’s gutting of national monuments, which would make it much harder to reverse this harmful action.

H.R. 3990

Another bill that would add to the assault on the country that surrounds Glen Canyon is Utah representative Rob Bishop’s H.R. 3990, which would gut the Antiquities Act. This bill would omit eligibility for monument protection for all objects “not made by humans”, including geology, rockscapes, canyons, etc. If these stipulations were removed from the Antiquities Act, many of the national monuments our country holds dear would never have been protected.

Contact your representative and tell them you oppose these bad bills!