glen canyon instituteDedicated to the restoration of Glen Canyon and a free flowing Colorado River.

GCI

History of the Bureau of Reclamation

When Major John Wesley Powell explored the Colorado River and its surrounding landscape over 130 years ago, he envisioned a place that could be settled, but not without consequences. His purpose was to study the arid lands and the landscape of the Colorado River basin, which resulted in recommendation of how western lands, and the Colorado River basin should be developed. He stated three major conclusions from his exploration and study of the Colorado River:

- The lands of the West have limits.

- The way the West is settled will have political consequences.

- Waters of the West should be managed by watersheds.

Powell’s recommendations on how settlement of the arid West should be managed were essentially ignored. Many scholars believe that most of the complex water policy problems that plague the West today would likely have been averted if a more careful approach that considered Powell’s recommendations was taken to settling the West.

In the beginning , settlement in the West was relatively easy and actually encouraged by the federal government. When settlers needed water they just diverted it from streams and rivers. Water rights in the West were determined by prior appropriation, which follows the mantra “first in time, first in right”. As the population of settlers started to grow, interest in diverting and damming rivers and streams began to grow. Pressure began to mount on the federal government to develop water resources and storage projects in the West to help subsidize farming and settlement. The phrase “reclamation” was applied in the early 1900s to irrigation projects meant to “reclaim” the arid lands for human use.

In 1901, after President Theodore Rooselvelt visited the West, the United States government officially got involved in “reclamation”. In 1902, the Reclamation Act became law, and created the Reclamation Service. Funding for reclamation projects came from public land revenues and other sources. Between 1902 and 1907 the Reclamation Service began 30 projects in the western states and Fredrick Haynes Newell was appointed the first director of the new bureau.

In 1922, the Colorado River Compact was signed by the seven states within the Colorado River basin, to divide and allocate the waters of the Colorado River. This would prove to be the most difficult and complex of the interstate compacts because of the complicated issue of dividing the shares of the Colorado River’s water between the basin states.

In 1923, the name of the Reclamation Service changed to the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) and in 1928 large appropriations began to flow to reclamation from the general funds of the United States. In 1928, the Boulder Canyon (Hoover Dam) Project was authorized. The first major catastrophe of the dam-building era occurred that same year, when the St. Francis Dam on the Santa Clara River (CA) failed immediately upon filling, sending a 100 ft wall of water downstream and killing 420 people.

During the Depression, Congress authorized over 40 more “New Deal” projects to provide public works jobs and to promote infrastructure development. The height of the dam-building era occurred during the time of the Depression and for thirty-five years after World War II. In 1936, Hoover Dam was completed (221 meters high), which set precedent for the BOR becoming a major hydroelectric producer. After the building of Hoover Dam, hydroelectric projects became a major feature of many reclamation projects, which had proved to be a major source of revenue for repaying Reclamation project costs: i.e. the “cash register” dams.

When the Colorado River Compact was first ratified, if was an agreement to divide the water of the “American Nile” between the seven states within its basin. The Colorado River Compact divided the river’s estimated 15 million acre-feet (MAF) of water equally between the upper and lower basins and established the cornerstone of the Law of the River. The Compact also provided that the Upper Basin states would not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry, Arizona to fall below 75 MAF for any period of ten consecutive years. In 1944, a treaty was signed to supply Mexico with a 1.5 MAF of water annually, thus obligating 16.5 MAF of Colorado River annually. Between 1928 and 1956 several new Acts and agreements governed the water development of the lower basin as California’s water needs grew with its steadily increasing population.

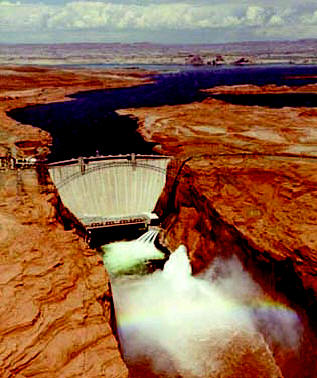

The Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP) Act was passed in 1956 providing a comprehensive upper basin-wide water development plan with the primary purpose of ensuring the upper basin’s water rights and meeting the 1922 Compact’s delivery requirement to the lower basin. The original CRSP proposal included the Echo Park and Split Mountain Dam projects, which would have backed Green River water up into Dinosaur National Mounument. As the symbolic birth of the modern Environmental Movement, public opposition organized to demand the omission of the “Dinosaur Dams”. As part of the unfortunate compromise with proponents of the CRSP, Glen Canyon Dam was allowed to be built without opposition. Glen Canyon Dam which was completed in 1963, was built as the keystone of the CRSP. The Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968 instructed the Secretary of Interior as how to manage the Long-Range Operating Criteria (LROC) of Glen Canyon Dam.

In 1969 the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was introduced, which didn’t have any impact on existing structures like Glen Canyon Dam, however, any future “major federal actions” regarding changes in dam operation or construction of new water projects would be subject to the NEPA process. The Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1972 on the other hand is directly relevant to dam operation. The ESA ordered all agencies to take action so as to protect and conserve endangered species and their ecosystems from extinction. Since all dams alter riparian ecosystems, passage of ESA caused changes in Reclamation management, which ultimately shifted their theory of management from construction of new water projects to operating and maintaining existing facilities over the next three decades.

At the core of the BuRec’s shift in management policy is Glen Canyon Dam and the Grand Canyon. Shortly after the dam’s completion, many concerns over the impacts of Glen Canyon Dam on the downstream ecosystem of the Grand Canyon began to surface. In an attempt to study these problems the BOR instituted Glen Canyon Environmental Studies (GCES) which revealed that dam operation were having negative impacts on the ecosystem. During the 1980s internal reforms within the BOR led to a shifting management philosophy of the BOR from a dam building agency to a dam management agency. Further reforms within the BOR led to the increased prioritization of environmental concerns in dam operations decisions.

As a major step toward greater environmental sensitivity within management decisions, the Secretary of the Interior ordered a Glen Canyon EIS in 1989 to study the problems. A few years later, the Grand Canyon Protection Act (GCPA) was passed, requiring that protection of the Grand Canyon be considered a priority in dam operation management. The following year, Dan Beard (Commissioner of the BOR) released the ‘93 Blueprint for Reform, which supported greater environmental concern through ecosystem management and increased collaborative decisionmaking involving non-traditional stakeholders. The completion of the Glen Canyon EIS in 1996 led to the Secretary of the Interior recommending a new operation plan for the dam that was designed to reduce impacts on downstream resources. Additionally, the Adaptive Management Program (AMP) was established to continue studying the impacts of the dam and make recommendations to the Secretary of the Interior as to how operations should be managed to reduce environmental impacts.

The present day Bureau of Reclamation currently operates and maintains more than 180 projects in the seventeen Western states. (Other water projects around the country are operated by the Army Corp of Engineers or privately). Reclamation projects provide water for about one-third of the population of the west for agricultural, municipal, and industrial uses. Furthermore, the BOR plays a role in hydroelectric power generation and marketing, recreation, natural and cultural resources, and flood control.

The future of the BOR shows that its budget and staffing levels are expected to decrease further into the 21st century. While a significant policy shift has occurred within the BOR, there are still major social hurdles on the path toward managing our nation’s rivers. With the ongoing drought in the West triggering great interest in a sustainable water supply, it is inevitable that the BOR will continue to evolve toward a more efficient and effective, sustainable Western water delivery system.